Resilience

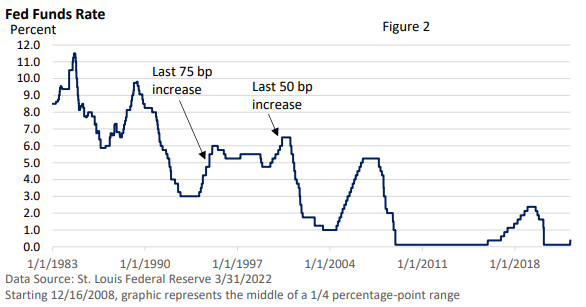

The Dow Jones Industrial Average is down 5.8% since its January 4th record high and the broader-based S&P 500 Index is off 5.5% since its January 3rd record high, according to St. Louis Federal Reserve market data through March 31.

If we measure the respective peaks to the most recent troughs of both indexes, the Dow lost 11.3% (January 4—March 8) and the S&P 500 Index lost 13.0% (January 3—March 8).

Selloffs are inevitable, and losing ground is hardly a reason to get excited, even if the recent pullback is modest.

Yet, given the Russian invasion of Ukraine, high inflation, soaring oil/gas prices, and rising rates from the Federal Reserve, stocks have been resilient in the face of stiff headwinds.

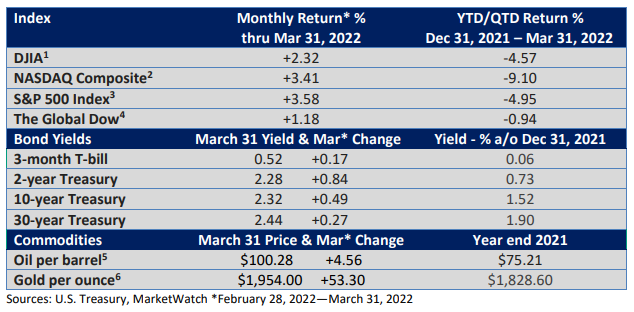

The most immediate impact of the war has been on gasoline prices, as illustrated by Figure 1.

The jump in gasoline prices will have an immediate impact on inflation, and we’ll see it reflected in the March Consumer Price Index, when it is released in mid-April.

But the overall economic impact is less certain. For every penny increase in the price of gas, U.S. consumer spending drops by $1.18 billion a year, according to an estimate from Federated Global Investment Management (Bloomberg).

For example, a $0.75 jump in gasoline, if maintained over a year, would hit spending by roughly $90 billion. But U.S. Gross Domestic Product is over $24 trillion, which would translate to less than 0.4%. It’s not insignificant, but by itself, it’s not enough to throw the economy into a recession.

Still, it’s not simply gasoline prices that are rising, and we may see some resistance to higher prices in general.

For investors, war generated an enormous amount of uncertainty, and stocks lost ground in the wake of the invasion. Yet, fighting continues and stocks have moved off the early March low.

Ukraine is far from an ideal situation, and how the war may unfold is a big unknown. But recently, there have been no significant developments that might negatively affect investor sentiment, and investors seem to be taking the apparent stalemate in stride.

Put another way, investors have gradually adapted to a new normal.

It’s not that we are immune to wanton acts of aggression by Russia. We’re not. Investors view geopolitical events through a very narrow prism. That is, how it may affect economic growth.

During March, economic activity appeared to accelerate. Weekly first-time claims for jobless benefits fell to a 52-year low per the Dept of Labor, and the U.S. BLS reported 431,00 new jobs.

The Federal Reserve rediscovers its purpose

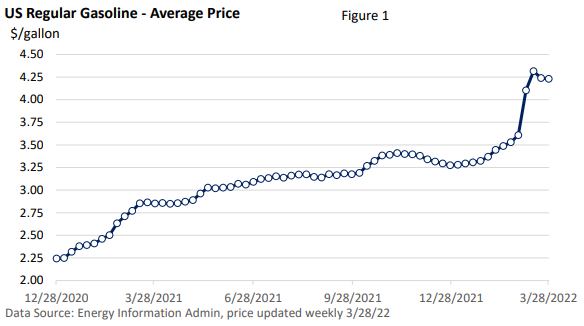

We haven’t seen a truly aggressive rate-hike cycle since 1994, when the Fed lifted the fed funds rate from 3% to 6% in one year—see Figure 2.

The last time we saw a 50 basis point ( 1 bp = 0.01%, so 50 basis points in this example = 0.50%) rate increase was in 2000.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the Fed raised the fed funds rate last month by 25 bp to a range of 0.25—0.50%.

The Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections released in March suggests the fed funds rate could rise to 1.75—2.00% by the end of the year. One closely followed gauge from the CME Group suggests a fed funds rate of 2.50—2.75% is possible by year-end.

Of course, these are simply projections and measures of sentiment at a point in time. They are based on the aggressive tone taken by Fed Chief Powell, recent comments by Fed officials, today’s tight labor market, and high inflation.

The Fed’s goal is to slow overall economic demand, which is putting upward pressure on prices, and reduce the huge number of job openings, which puts upward pressure on wages. Both variables raise costs for businesses, which can get added to the price of retail goods.

Few would turn down a big raise. That’s understandable. But the Fed sees a wage-price spiral and too-strong demand as inflationary.

Of course, to bring down inflation, the Fed will need help from the supply chain, but the war in Ukraine will likely exacerbate problems, at least over the shorter term.

During the mid-1960s, mid-1980s, and mid-1990s, the Fed pre-emptively acted against the potential of higher inflation and engineered what analysts call a ‘soft landing,’ which simply means it didn’t throw the economy into a recession.

Today, the economy is creating plenty of jobs, but inflation is higher, which makes the Fed’s task more challenging.

Why is it more challenging? High inflation will likely require more aggressive rate increases, which might slow the economy too quickly.

The Fed is not acting proactively against the possibility of higher inflation. Instead, it is reacting to higher prices, hoping to bring inflation back to its 2% target without a recession, i.e., a hard landing.