Investors Look Beyond Inflation, Rate Hikes, and Recession Fears

Inflation is high, the Federal Reserve is hiking interest rates, Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which is the broadest measure of economic activity, is declining. Yet, the stock market had a significant rebound in July.

Investors attempt to price in events before they hit the headlines. We saw it in the first half of the year. But does July’s rally herald better economic news, or is it simply a bear market rally?

Inflation is a big problem, no question about it. In June, the Consumer Price Index hit 9.1%, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). It’s the worst reading in over 40 years.

However, gasoline prices fell in July, commodity prices are down, and there are some cautiously encouraging signs that inflation may finally be peaking.

It doesn’t necessarily mean that inflation will slow sharply. But if the worst is behind us (a big maybe), it would be encouraging news for investors.

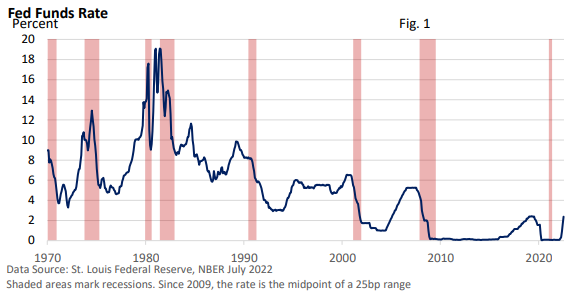

Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve just hiked the fed funds rate by 75 basis points (bp, 1 bp = 0.01%) to a range of 2.25-2.50%.

Since early May, the Fed has boosted the fed funds rate by 200 bp. It’s the most aggressive series of rate increases since early 1982—see Figure 1.

In the past, the Fed seemed willing to throw a lifeline to investors when market declines turned ugly. Not today. It’s a different environment, as the Fed seems intent on squashing the very inflation it helped create.

Yet, it would be unfair to blame today’s inflationary environment completely on the central bank. Trillions of dollars in fiscal stimulus, pandemic lockdowns, and supply chain woes have also contributed to inflation.

During his July 27 press conference, Fed Chief Jerome Powell forcefully argued the Fed will maintain its course until it sees “compelling evidence that inflation is moving down, consistent with inflation returning to 2%.”

Yet, he hinted that the Fed might slow its pace of rate increases later in the year. Investors took that as an encouraging sign. Still, it’s highly dependent on inflation.

Lastly, GDP is down two-straight quarters: a 1.6% annualized drop in Q1 and a 0.9% annualized decline in Q2, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

It meets the common and simple definition of a recession. But are we in a recession?

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) makes that determination in the U.S. It can take months for the NBER to declare and backdate the start of a recession.

The NBER defines a recession as “a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts more than a few months.”

Well, GDP is down for more than a few months, but to contend that any decline is significant and is spread across the economy is far more problematic.

While business spending fell in Q2 and residential construction got clobbered, consumer spending, which accounts for 70% of GDP, increased, albeit at a slower pace than Q1.

Over the last six months through June, the U.S. BLS said payroll growth has averaged 457,000 per month. Layoffs, not significant job growth, mark recessions.

While GDP may not tell the entire story, economic growth has significantly slowed, wages are not keeping up with inflation, and stocks stumbled in the first half of the year.

Consequently, it’s a gloomy number, even if the economy hasn’t yet met the NBER’s strict definition. Perhaps the term stagflation, stagnate economic growth + inflation, more closely describes today’s environment.

Bottom Line

Investors attempt to price in and anticipate events by roughly six to nine months. In the first half of the year, investors correctly anticipated the uncertain economic environment.

Investors also seem to be pricing in a mild recession.

The Conference Board, which releases the monthly Leading Economic Index (LEI), believes “a recession around the end of this year and early next is now likely” after its Index fell for four consecutive months (through June). The LEI is designed to foreshadow economic trends.

A more pronounced economic downturn, if it were to occur, probably hasn’t been factored in by investors. But would the Fed blink in the face of a recession? Powell side-stepped the question.

Another series of unusually large rate hikes may not be priced in either. The same can be said of an even faster rate of inflation.

Yet, no one rings a bell when the market hits bottom. Instead, investors attempt to sniff out better news before it reaches the headlines. That helps describe what we saw last month.

If you have questions or would like to talk, we are only a phone call or email away.