Powell’s Volcker Moment

Paul Volcker headed up the Federal Reserve between 1979 and 1987. He is widely credited with squashing the inflation that seeped into nearly every corner of the economy in the 1970s.

But the medicine the Fed force-fed us was harsh. The Fed pushed up its key rate, the fed funds rate, to almost 20% by the end of 1980, per the St. Louis Federal Reserve. The jobless rate rose to nearly 11% in late 1982, which at the time was the highest since the 1930s.

It broke the back of inflation. But the price was steep, as the U.S. fell into a deep recession.

Today, inflation is high, but isn’t as embedded in the economy as it was in the 1970s. So far, the medicine that’s needed is unlikely to be as harsh as during the early Volcker years.

However, like the jump in interest rates that stifled demand for goods, services, and workers, the Fed is hoping to employ lessons learned in the 1970s without a steep recession.

For starters, the Fed quickly jettisoned its zero-rate money policy, it’s no longer talking ‘transitory inflation,’ and it wants to avoid the stop and go attack on the wage/price spiral in the 1970s, which failed to quell inflation and led to a harsh policy response from Volcker’s Fed.

In other words, the longer inflation persists—the thinking goes—the more difficult it is to put the inflation genie back in the bottle.

Before we go on, let’s acknowledge that Powell and the highly credentialed economists at the Fed failed to forecast the persistent rise in inflation and failed to react last year. Today, they are playing catchup.

While it would be unfair to blame today’s inflationary environment completely on the central bank—trillions of dollars in fiscal stimulus, pandemic lockdowns, and supply chain woes have also contributed to the problem, they are tasked with cleaning up the mess.

Powell’s Fed is well aware of the mistakes that helped lead to the prolonged period of rising prices in the 1970s, and central bankers don’t want a repeat.

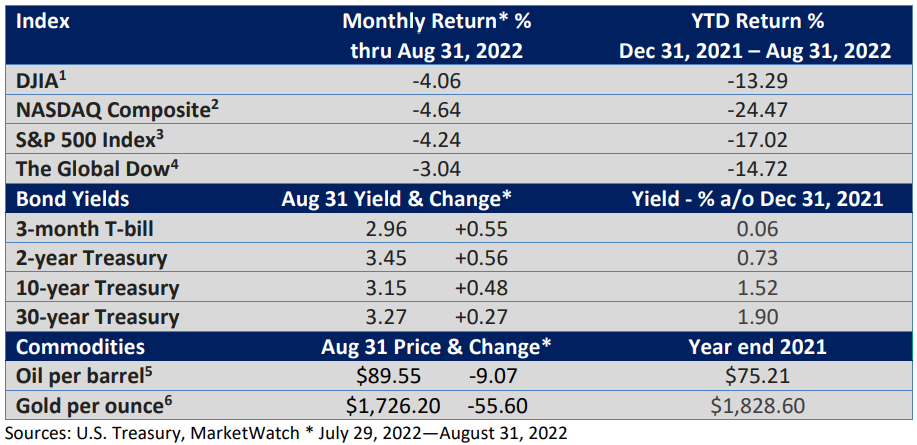

Yet, over the short term, 2022 has been a period of heightened uncertainty for investors. That said, at the end of August, Powell vigorously reiterated the Fed’s commitment to bringing inflation back down.

In a brief speech that lasted fewer than 9 minutes, Powell called the Fed’s goal of price stability its “overarching focus right now.”

“Restoring price stability will take some time and requires using our tools forcefully to bring demand and supply into better balance,” he said.

Powell added that softer economic growth will “bring some pain to households and businesses. These are the unfortunate costs of reducing inflation. But a failure to restore price stability would mean far greater pain.”

Powell’s use of the word ‘pain’ is unusual for a Fed chief. However, in no uncertain terms, he wanted to communicate that the Fed is resolute in its fight and will do what’s needed to force inflation back to the Fed’s 2% target.

Threshold for pain

How much pain the Fed might inflict on the economy is unknown. Would the Fed blink if anything more than a mild recession took hold? Is there an economic line in the sand?

The Fed’s not saying. If it revealed a line it won’t cross, its credibility would further come into question. Yet, a squash-inflation-at-all-costs mentality could bring a political backlash.

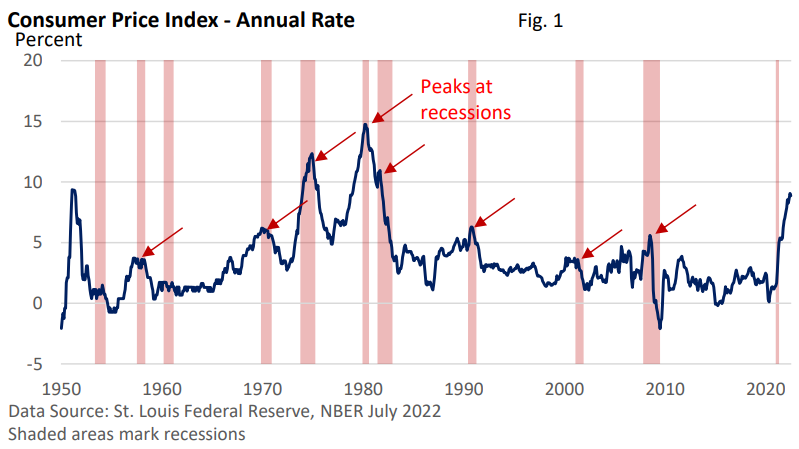

Please review Figure 1. Note that inflation has historically peaked during a recession and eases in the early stages of an economic recovery.

Recessions blunt demand for goods and services, commodities, and labor. Businesses typically struggle to raise prices during a recession, while a rise in unemployment puts a lid on wage hikes and cost pressures. It wrings inflation out of the economy. In the months that follow a recession, excess capacity tends to keep inflation low.

When we have seen inflation slow outside a recession, it occurred amid a sharp but temporary drop in oil prices (mid-1980s and late 1990s), or the sharp productivity gains of the 1990s.

Today, the Fed is turning to what it believes is its tried-and-true anti-inflation playbook.

During the early part of August, investors seemed optimistic the Fed might cut rates next year. A host of Fed speakers and Powell blunted such hopes, sparking a fresh round of volatility.

Bottom line

Powell mentioned pain. Today, the Fed is trying to stifle demand for goods and services and significantly slow wage increases. The high number of job openings leaves it some wiggle room that might help prevent a recession or anything more than a mild recession.

The Fed also wants to bring down commodity prices and lower prices for housing and financial assets. The rate of inflation may have already peaked, but the Fed doesn’t want to declare victory until its convinced price stability is within its grasp.