Inflation Makes a Play, Investors Ignore

Just when you thought it was safe to go back into the department store, inflation surprised to the upside last month!

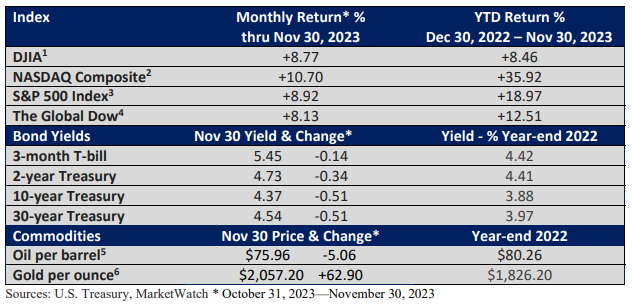

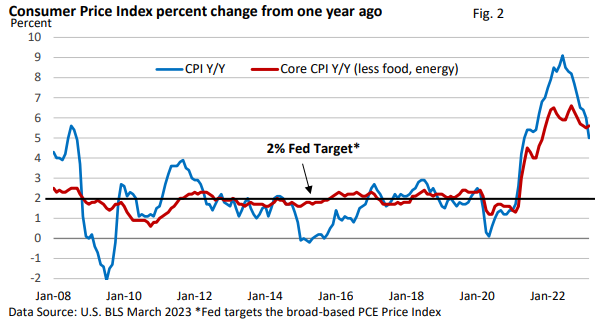

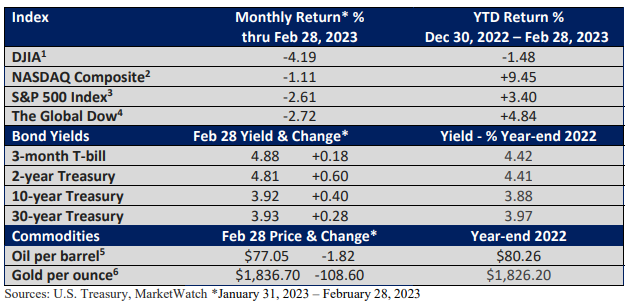

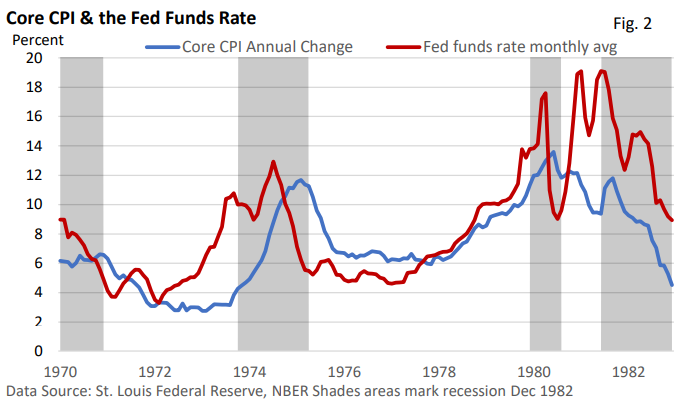

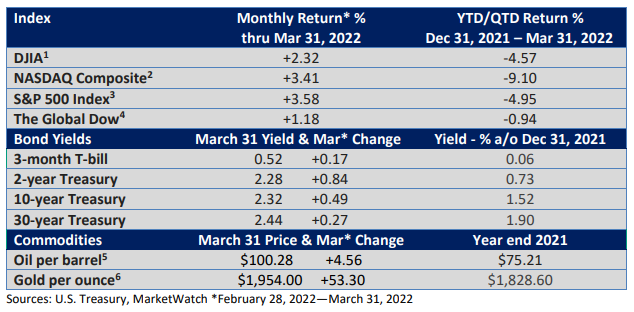

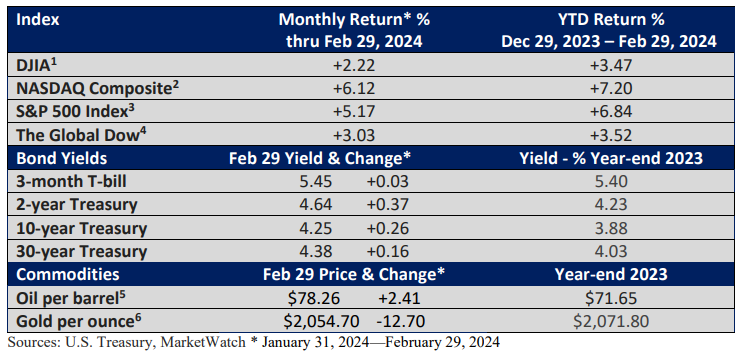

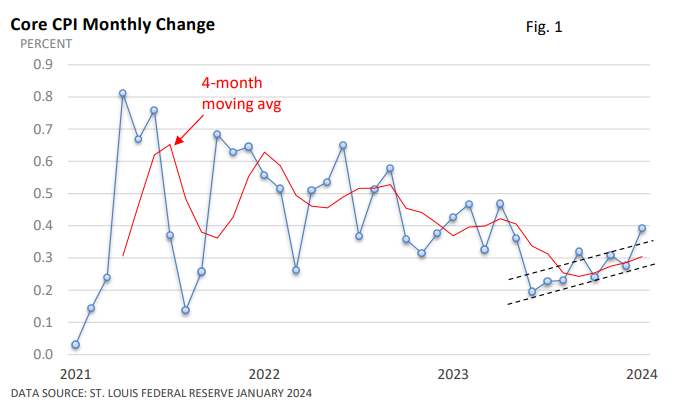

As reported in mid-February, the Consumer Price Index(CPI) rose 0.3% in January, and the core CPI, which minuses out food and energy, rose 0.4% per the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

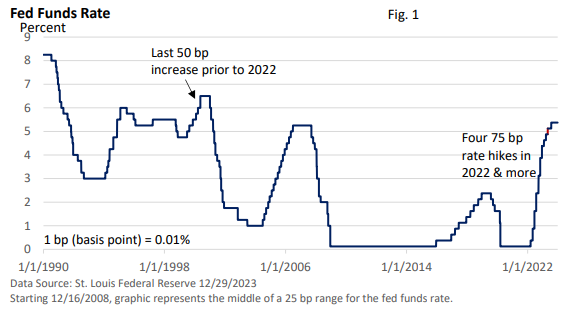

According to the Wall Street Journal, both measures topped expectations by 0.1%. On an annual basis, the CPI is up 3.1% and the core CPI is up 3.9%. Neither comes close to the Federal Reserve’s definition of price stability, which it characterizes as a 2% annual rate.

Inflation had been moving in the right direction, and January is a reminder that unwanted surprises are to be expected.

Why focus on core inflation?

Groceries and energy are a big part of the cost of living. Besides, the CPI is lower today when food and energy are included.

Food and energy can be volatile. So, economists like focusing on the core rate as it provides a better picture of underlying inflation trends.

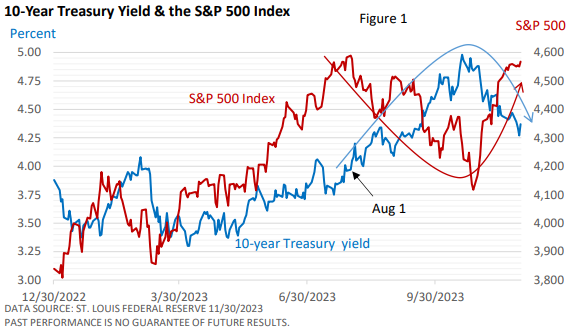

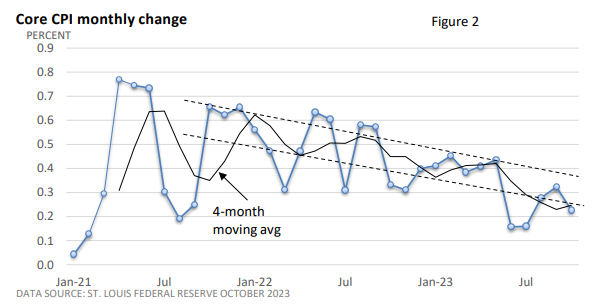

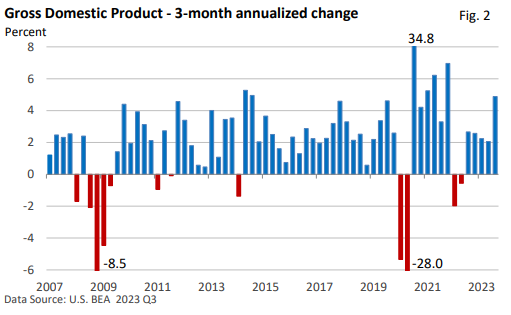

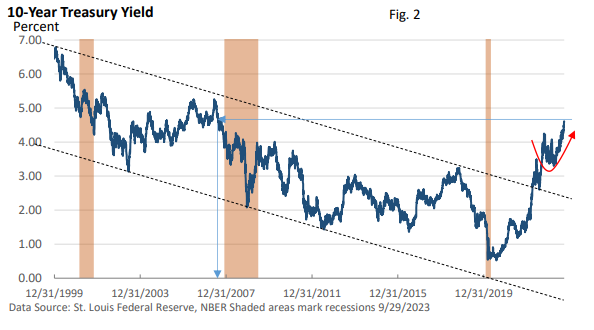

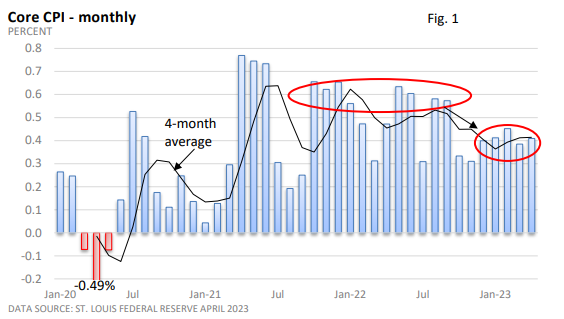

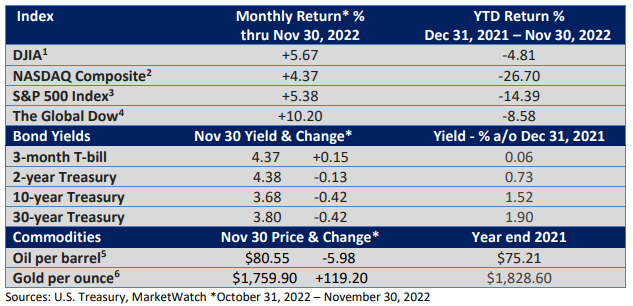

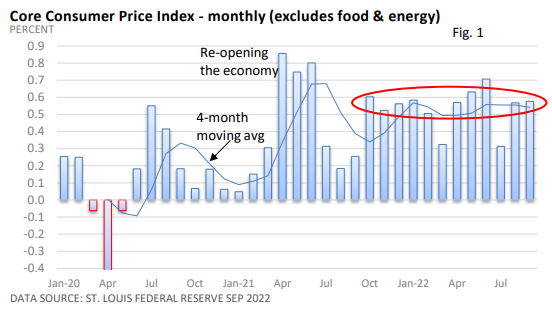

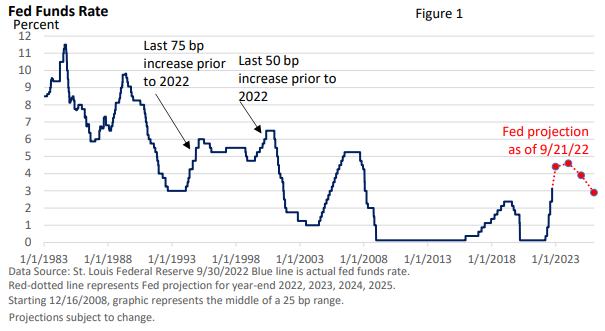

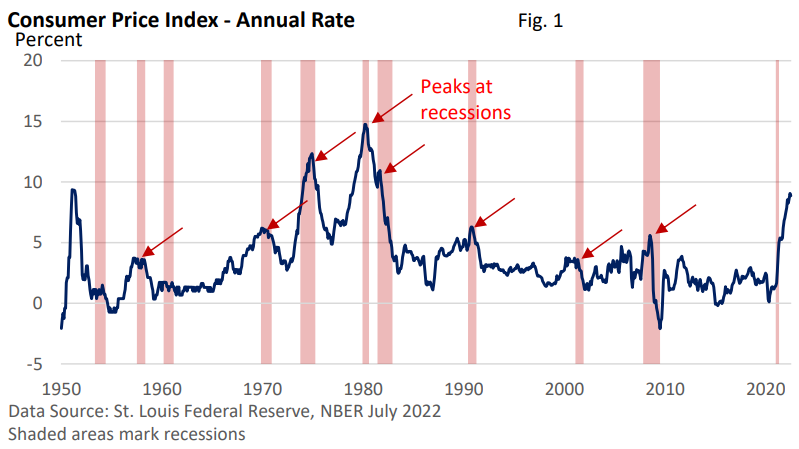

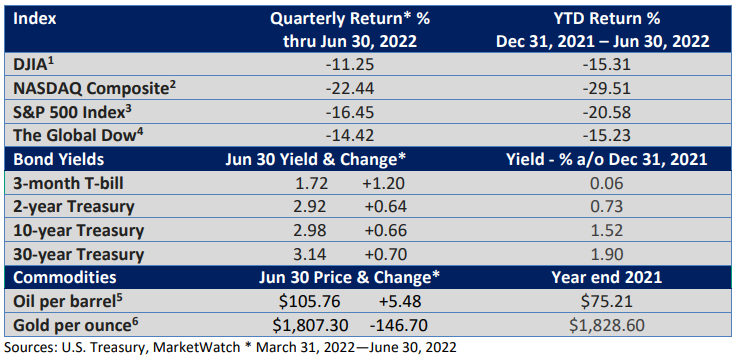

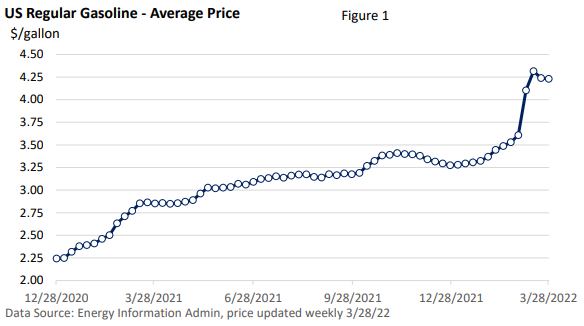

As Figure 1 illustrates, inflation rose at its fastest pace since April. More recently, progress toward a more stable price level has stalled, and the rate has ticked higher.

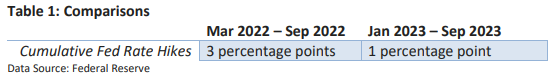

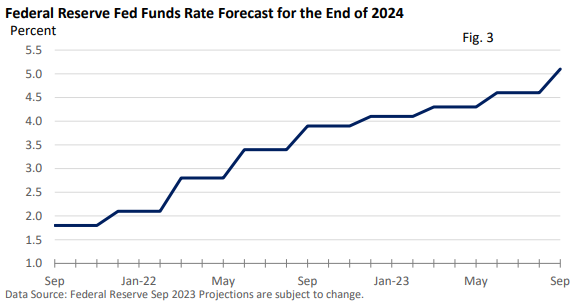

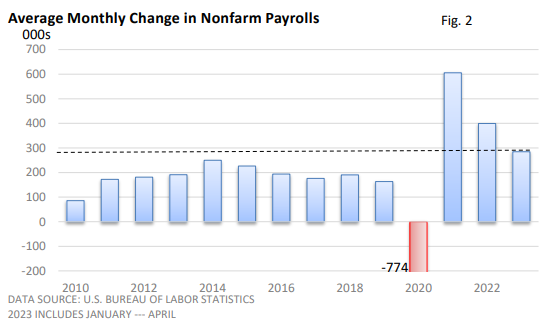

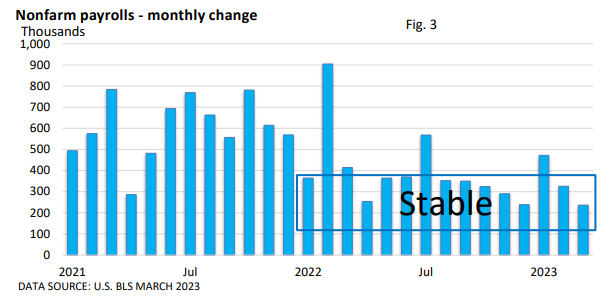

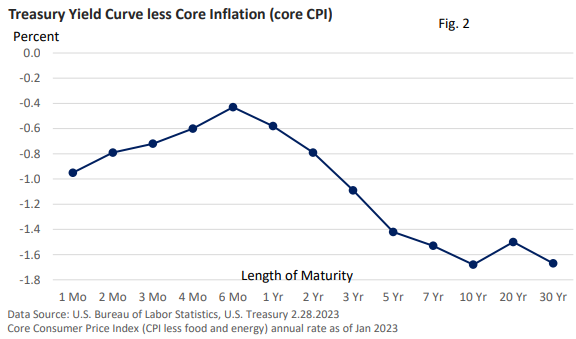

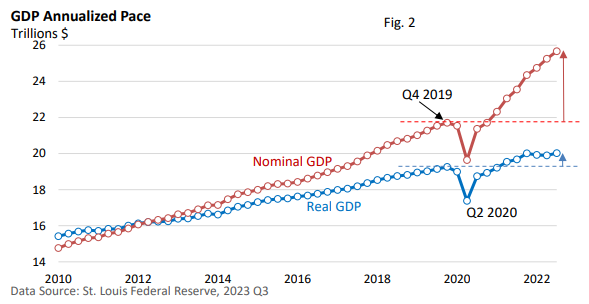

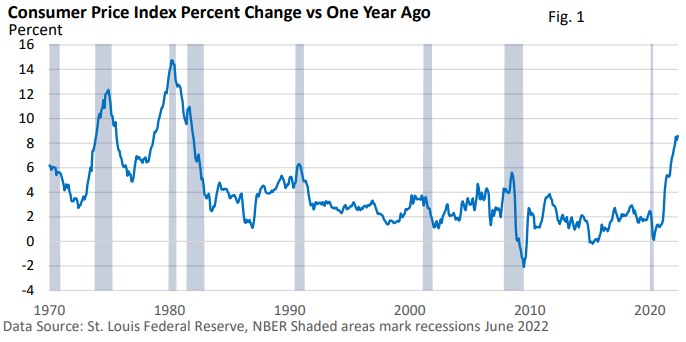

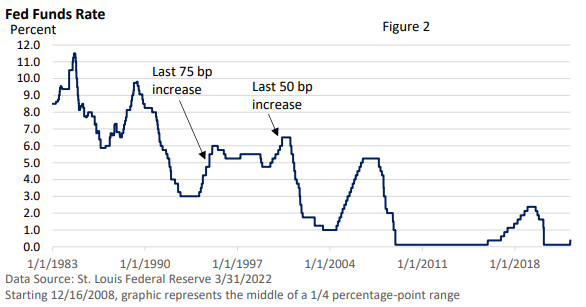

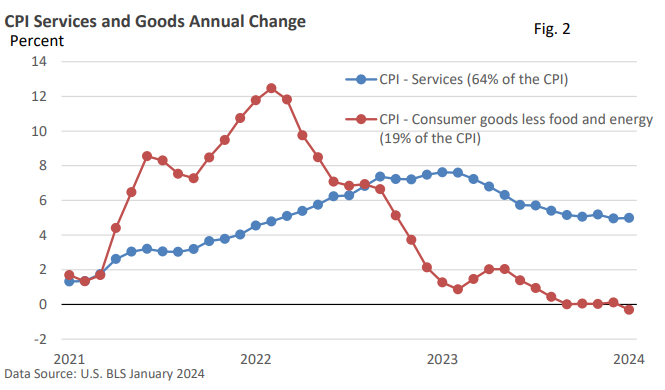

Figure 2 highlights what’s under the hood.

In 2021, the price of consumer goods jumped amid supply chain woes, super-low interest rates, and government payments to families and individuals that flowed into consumer goods. But a much-improved supply chain has eased bottlenecks, and prices for goods have stabilized.

Services, however, are much stickier and are stuck near 5%.

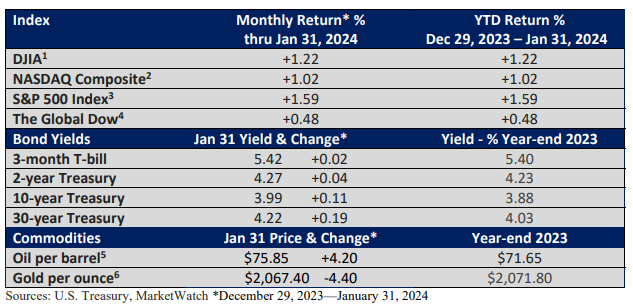

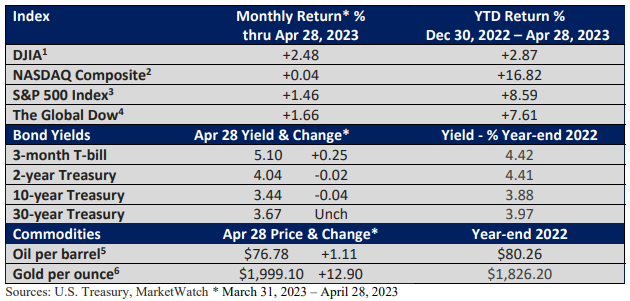

Investors side-stepped inflation worries last month

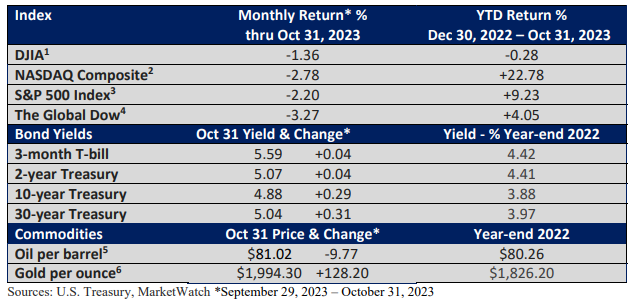

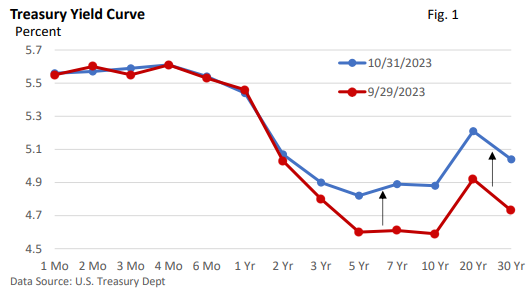

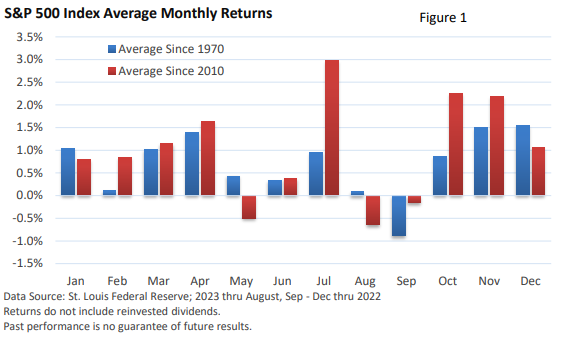

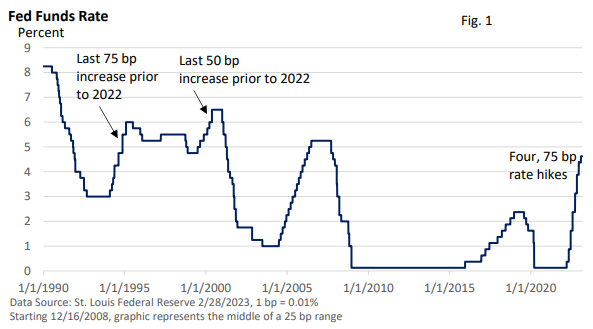

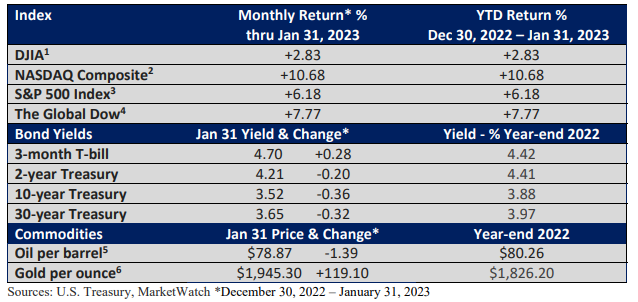

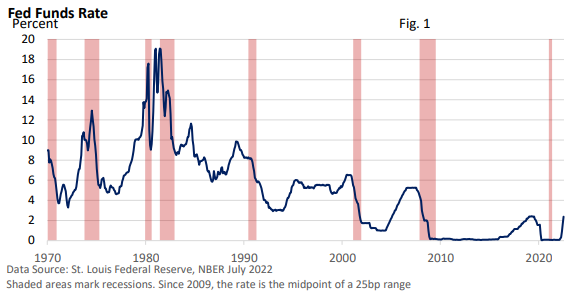

A strong January employment report, coupled with a lack of progress in inflation, threw cold water on talk of a March rate cut by the Fed.

One key measure from the CME Group now projects three quarter-point rate cuts this year versus six or seven in January. That is a considerable difference.

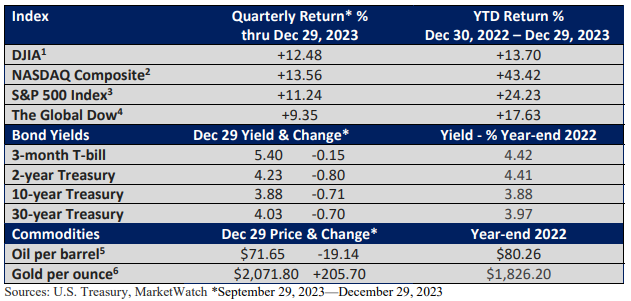

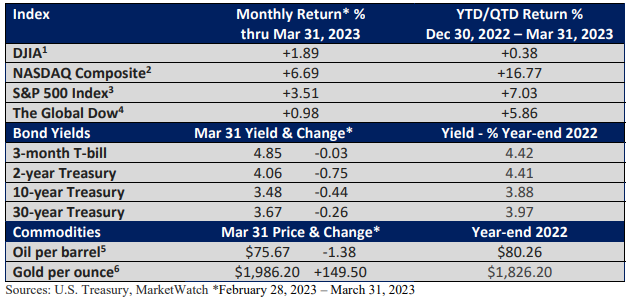

Nonetheless, a more moderate path did little to dampen enthusiasm for stocks last month.

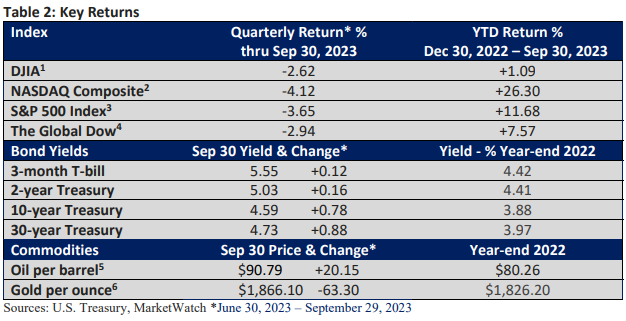

The S&P 500 Index and the Dow Jones Industrials set new highs late in the month, and the Nasdaq Composite closed at a new high at month’s end, eclipsing its previous high over two years ago (MarketWatch data).

Credit a growing economy, rising corporate profits, and an appetite for AI-related stocks among investors. Notably, stocks pushed higher even as bond yields rose last month.

Yet, according to Bloomberg News, a few investors are starting to factor in a possible rate hike or hikes this year as the Fed struggles to steer the economy toward a soft landing.

Because rate increases aren’t expected this year, any talk of further tightening by Fed officials, if it were to surface, would likely create some volatility.

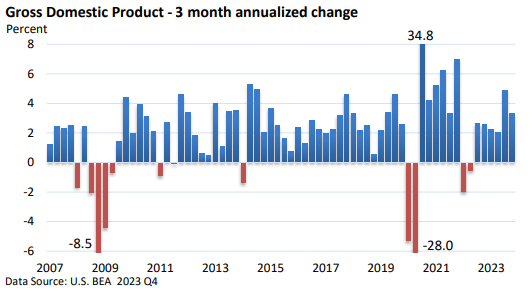

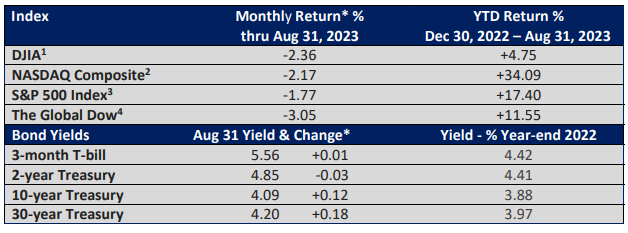

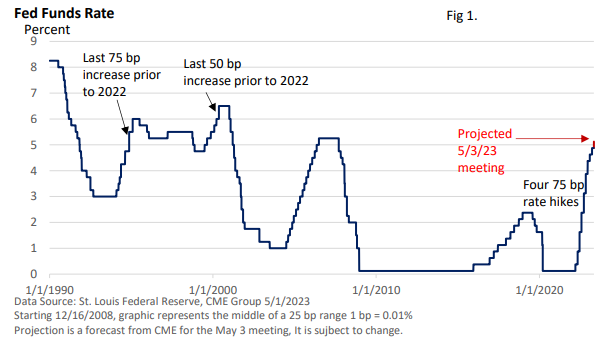

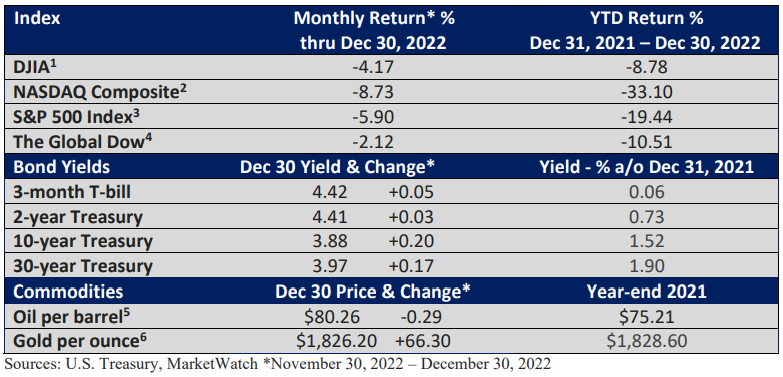

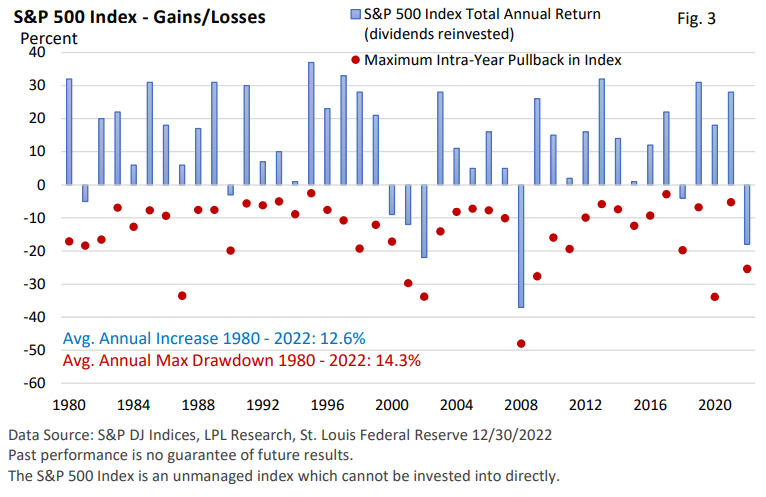

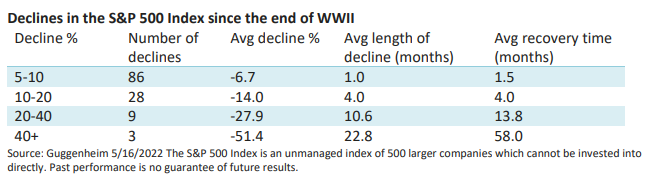

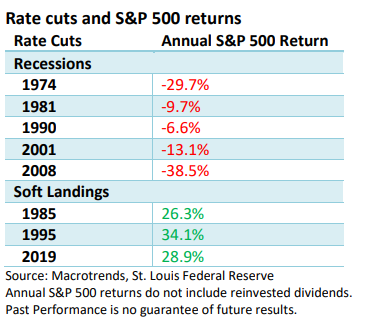

But, as the table below suggests, rate cuts alone don’t fuel market gains when the reductions are in reaction to a recession.

In contrast, profit growth typically accompanies the soft-landing scenario that avoids a recession. In that case, lower interest rates and rising profits have historically aided stocks.

But any benefit from falling interest rates that coincide with a recession has historically been offset by stiff headwinds from falling profits, which is typical of a recession.

Final thoughts

Perhaps the 0.4% rise in the core CPI was an aberration tied to the calendar. Some firms may see January as a good time to hike prices. You know, turn the page on the calendar, raise prices. Or, price hikes come in response to annual wage hikes. We’ve seen it before.

Besides, the road to price stability was never going to be a straight line. Sometimes, you expect a zig, and instead, it zags.

Unfortunately, the recent trend highlights more zags than zigs, as illustrated in Figure 1. That suggests the last mile to price stability may be the hardest.

Yet, that didn’t discourage investors last month.

Please let me know if you have questions or would like to discuss any other matters.